This is Part 2 in the series “All About Apps”.

App stores must not be viewed as simply distribution outlets for apps but as a new business model. That model centers on building an attractive business platform and leveraging its network effects to reshape the competitive landscape to the advantage of leading app store operators.

Mobile apps are downloaded mainly from app stores, e.g., three out of four iPhone apps from Apple App Store and more than half of Android apps from Android Market (VisionMobile, 2011). These stores generated approximately 7 billion downloads for $4.1 billion in revenue in 2009 and are projected to reach 50 billion downloads for $17.5 billion in revenue by 2012 (Chetan Sharma Consulting, 2010). There are 103 app stores, according to the Wireless Industry Partnetship (WIP, 2010). Only a few stores (among them, Apple App Store, Google Android Market, Androlib and GetJar) have reached the level of one billion plus downloads. For developers, app stores offer the widest market reach, far ahead of other distribution channels (e.g., own websites). However, each store has its own developer sign-up, app submission process, app certification and approval criteria, revenue model options, and payment settlement terms. Developers may find the costs of distributing apps via multiple stores, even for the same development platform, add up quickly and are thus hesistant to go beyond a few stores.

Mobile apps are downloaded mainly from app stores, e.g., three out of four iPhone apps from Apple App Store and more than half of Android apps from Android Market (VisionMobile, 2011). These stores generated approximately 7 billion downloads for $4.1 billion in revenue in 2009 and are projected to reach 50 billion downloads for $17.5 billion in revenue by 2012 (Chetan Sharma Consulting, 2010). There are 103 app stores, according to the Wireless Industry Partnetship (WIP, 2010). Only a few stores (among them, Apple App Store, Google Android Market, Androlib and GetJar) have reached the level of one billion plus downloads. For developers, app stores offer the widest market reach, far ahead of other distribution channels (e.g., own websites). However, each store has its own developer sign-up, app submission process, app certification and approval criteria, revenue model options, and payment settlement terms. Developers may find the costs of distributing apps via multiple stores, even for the same development platform, add up quickly and are thus hesistant to go beyond a few stores.

App stores are run by either:

- mobile device producers (aka original equipmentmanufacturers [OEMs], e.g., Dell Mobile Application Store, BlackBerry App World, Nokia Ovi and Samsung Apps),

- mobile operating system developers (e.g., Apple App Store, Android Market and Windows Marketplace for Mobile),

- mobile network operators (MNOs, aka phone carriers, e.g., Orange App Shop and Verizon Apps) or

- independent intermediaries (e.g., Amazon Appstore, Getjar and Appitalism).

By design, some stores carry only native apps for a particular operating system (e.g., Android Market, Apple App Store, BlackBerry App World and Nokia Ovi Store) while others offer apps for multiple platforms (e.g., Getjar, Mobango and Hallmark).

App stores embody a new business model that capitalizes on the trends toward technology and media convergence, leverages a different economic driver and reshapes industry landscape to the advantage of leading app store operators.

Technology and media convergence. Traditionally, industry boundary was clear cut and key market players easily identified. In the hardware sector, the phone industry was led by global OEMs (e.g., Nokia, Samsung, LG, RIM, Sony Ericsson and Motorola). Their focus was on the hardware; they typically treated software (operating system and applications) as a supporting elements necessary for the hardware to function rather than a key market differentiator. In introducing the iPhone and its associated App Store, Apple sees the business quite differently: traditional industry boundary no longer matters when several technologies are converging on a single piece of hardware. The iPhone is not just a mobile phone; it is also a media player, a game device, a web browser and a networked computer (though with only limited computing capabilities).

From scale economies to network effect. Apple views its operation system iOS not as a piece of software on which its iPhone hardware runs but as a platform serving a multi-sided market. In the old mobile phone business, the market was viewed as single-sided – the OEMs served only one side of the market (phone users); third-party developers and their applications were very few in number and limited to providing some basic functionalities for the hardware as specified by the OEMs. One OEM saw other OEMs as its competitors. Their business model typically relied on supply-side economies of scale – pricing aggressively to boost sales; higher sale volume would lead to larger production scale, lower unit costs and in turn even lower prices to boost sales further. By contrast, the iOS platform, with the App Store being its business element, mediates interactions and transactions between several groups of market partipants who were, except the phone users, traditionally not key players in the mobile phone business. Each group is attracted to the platform by the vast opportunities to monetize on the products and services they can offer to participants on the other side or sides of the market, e.g., independent developers by the large base of iPhone users who may download their apps, and iPhone users by the large and growing number of apps and media sources that enrich their user experience. The value of a platform to any group of market participants depends on the number of participants on the other side or sides of the market. This is known as the (cross-side) network effect. It tends to propel a market leader already ahead of its competitors further ahead. There is little benefits for market participants to join a trailing platform when many participants on the other side(s) already join the leading platform. Few developers are interested in building apps for HP Touchpad, which runs on HP WebOS, when most users prefer Apple iPad; in absence of any other compelling incentive, few users would be interested in buying the Touchpad when most apps are being built for the iOS (and Android) instead.

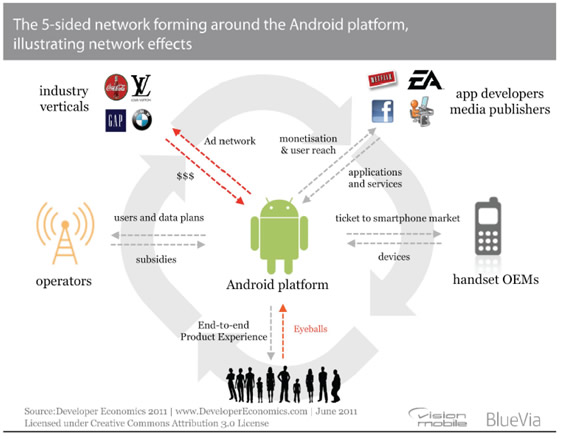

Altered competitive landscape. Apple’s rival, Google, has been quick to recognize the new business model centering on leveraging the network effects. It leads the Open Handset Alliance, a consortium of many hardware, software and telecommunication companies, in developing Android as an operating system for mobile devices. It seeks to capitalize on Android not simply as an operating system for mobile devices but as a platform to capture the lion’s share of a multi-sided market emerging from the convergence of several technologies and media. Unlike Apple, it does not offer mobile devices but its partners in the Open Handset Alliance (e.g., Samsung, LG, Sony Ericsson and Toshiba) do. The graphic below depicts Android as a platform serving a five-sided market.

- On the one side are app developers and media publishers who seek to monetize their apps and media content through downloads, subscription and/or advertising revenues. They are attracted to Android by the potentially large number of devices running on this operating system.

- On another side are the OEMs who see the bennefit of having a common (thus popular) operating system that (a) lets them quickly enter the smartphone business without having to develop an operatingn system of their own and (b) can quickly attract many app developers.

- On the third side are mobile device users who are drawn by the large number of available apps giving the hardware a fuller set of functionalities and offering them rich sources of media content.

- On the fourth side are network operators (or phone carriers, e.g., Verizon and ATT) who see a huge pool of subscribers for their service and data plans. They also see the growing libraries of media content being made available for mobile devices as a new source of demand growth for higher-price, unlimited data plans. They are eager to sign up subscribers by offering subsidized prices for mobile devices so as to lower the initial cost of hardware acquisition.

- On the fifth side are marketers. They view this huge pool of mobile device users, who are individually identifiable and geographically located, as an attractive target for their ads and services.

For Apple’s iOS, the picture is quite similar. The main difference lies in the second side of this five-sided platform – mobile device producers. All devices running iOS are Apple’s products. Still the network effects work the same way. All the other sides are atttracted to iOS by the large and fast expanding population of iOS devices (iPhone and iPad) in use.

In this emerging multi-sided market, the rising stars are the few players that can attract the most apps for their platforms and in turn enrich user experience and generate greater value to other market participants. Success in this regard enables these platform operators to gain market shares without resorting to price competition. Apple (with its iOS) and Google (with its Android) are two such rising stars. Apple has been charging premium prices on its iPhone and iPads. Meanwhile, Google focuses on making money from advertising and location-based services, leaving it up to the OEMs to flood the market with affordable Android smartphones and mobile devices; the more ubiquitous these devices become, the more money Google is going to make from its advertising business. On the decline are some former leading OEMs (e.g., Motorola and Sony Erickson) who have stayed too long with the old-style strategy of exploiting supply-side economies of scale to drive down unit costs and prices. Unfortunately for them, the consumers buying smartphones and tablets in recent years are much more willing to pay for design novelty, rich media consumption experience and business productivity tools than for stripped-down devices at a low price. Other OEMs may have rested on the large size of their customer base and thus not been active in attracting app developers. Their platforms (e.g., Blackberry by RIM and Symbianby Nokia) trail far behind Android and iOS in app count.